The scientific process of hypothesis testing and experimentation to arrive at knowledge describes exactly the process of faith building, because faith is "the evidence of things not seen". Atheists and the like interpret Paul's words to mean somehow blind belief stands in for evidence, but that's just backwards from his plain meaning. The thing is that in this world there are some things so difficult to prove fully, even though there's plenty of evidence for them, that people can go a long way in their ongoing process of faithful experimentation before they are brought to a point where the evidence no longer supports their hypothesis. I daresay the vast majority of humankind has died without understanding basic truths about God, about His requirements for Celestial life, etc.

LDS doctrine makes room for these. The Book of Mormon conceives of life as a testing period, just as the Bible obviously does. And it talks plainly of a waiting place, a time between death and resurrection, however long that may be, when a spirit continues its existence but has no body to act upon, therefore its test period is technically over. This waiting period is a time when the intelligences that are spirits have means of communication, but not means for restitution of wrongs (which is part of repentance). They may be taught, even change their minds, but not complete a full repentance because such requires a body to enact. Faithful, authorized teachers are organized and sent to those spirits who may still be open to mind-changing, and who can expect to be judged according to their deeds in the flesh, but in light of the truth their minds received in this "spirit world".

For those still living, however, there is ample occasion to keep one's convictions, to continue in one's faith, to live according to one's "knowledge" in the direction the content of that knowledge takes them.

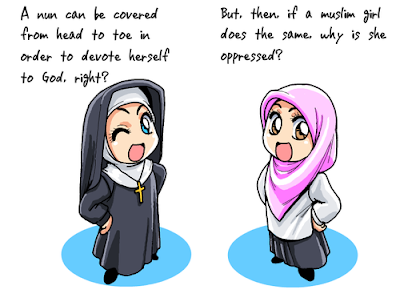

Because faith, hypotheses, knowledge, have a direction AND a magnitude, people can develop great faith in directions that end in a cul-de-sac. My first exposure to this idea was at a talk where the speaker told the story of being reprimanded for making fun of nuns. The nuns had devoted their lives to the doctrines they espoused, had gone celibate, and had taken to wearing distinctively pious clothing all as a method of service to God. The young man was right to ridicule them, from his perspective, because according to HIS beliefs, the nuns were all merely "useful idiots" to their church leaders, and would ultimately be proven to be cheated. But the father was wise to correct the son: it's not their devotion that's the problem, just the direction of the devotion.

I learned more about this on my mission in a 40% Muslim country. I disagree with a great deal of the lynch-pin doctrines of Islam, but if a set of beliefs can produce a billion people who make ablations and stop all activities to pray at 5 specified times during the day, then it also has the power to solidify and anchor those beliefs much more strongly than most Christian denominations can, since all most main-stream Christianity requires is a mere once-in-a-lifetime confession. I wish I had the faith to pray 5 times per day.

Sadly, this principle also operates with political beliefs too. And although I can praise people for the magnitude of their faith in certain beliefs, sometimes a corrective in direction is required as well. And the principle of faith as a vector helps one understand how people can hold on to untrue beliefs, but doesn't have anything to say about how to correct them. Eventually, people can end up, as one anonymous internet de-bunker put it: "seeing what they believe, and not the other way around."

I'm gearing up to tackle some Alex Jones in some of my future posts...

Comments